|

|

|

|

||||||

| Interview with a New Orleans music man | ||||||

| Janet Boyle | ||||||

|

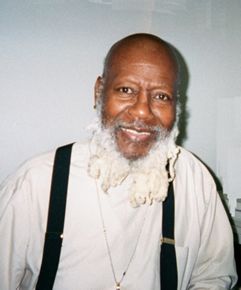

The first thing you notice about Harold Battiste is the fleecy white beard that wreaths his face.Then the eyes, large, soft, and brown, intelligent and slightly amused.He sits behind the desk in his small UNO office, where testimonies to his life’s work in music abound. Behind the desk are shelves full of audio tapes, above which hang photos of himself with Sonny and Cher and a Louisiana Cultural Vistas cover on which he is featured above the headline,"Louisiana's Music Legends." To the left stands a six-foot bookshelf packed with 33 1/3 RPM record albums, a collection that would probably make an aficionado of old records weep with envy. Not a single album leans; all stand straight, neat, and tight together, with no room for more.On the wall on the opposite side of the desk, five gold records gleam beside several placques recognizing his accomplishments. Farther along down the wall a frame houses a sheet of paper with five words handwritten on it "Yes, but can he play"-- question that I will later learn fits in with his philosophy about music. Harold Battiste spent his early childhood in an Uptown neighborhood bounded by St. Charles, Claiborne, Jackson, and Louisiana Avenues[link?].With the neighborhood activities, it was hard for him not to become involved with music in some way, though he doesn’t see his singing in his church choir as having “counted” because that was something you simply did.There was a piano in his home, but no one played it except an occasional guest.Though his father played the clarinet, Battiste began showing an interest in music on his own when he was seven or eight, and listening to the radio, would beat out rhythms on his mother's furniture.He laughingly describes the fork marks he put into his mother’s cedar chest.He said his mother 'got scared" when he picked out a melody on the piano, because 'being a musician wasn’t the most promising thing," and when the family later moved into a housing project she told him that pianos weren’t allowed and so they left it behind.His father, who owned a tailor shop on Rampart St. later got the boy a clarinet. In his high school band, he wasn’t the best clarinetist, but he wanted recognition, so he transcribed a recording and took it to his band director, who had the band play it.The remarkable accuracy of the arrangement prompted the band leader to ad vise the boy to get a Glenn Miller book on arranging from Werleins [link?].By this time he knew he wanted to be a musician, thought he did not know that he could be employed as an arranger.His mother wanted him to be a doctor; they compromised and he graduated from Dillard in 1952 in music education. His first job in de Ridder brought him both the wonderful experience of implementing a music program and his first awareness of racism when he accompanied his principal to the School Board to request money for uniforms.The disrespect and refusal they encountered did not stop them from raising the money for uniforms on their own.Three years later he came to New Orleans as an itnerant music teacher, where he "had problems again." One supervisor told him that parents just wanted to hear the kids play a few songs, to stop wasting so much time teaching kids to read music."Why shouldn’t I teach them to read music--they do it at Warren Easton." (Easton was an all-white school at the time.) He was brought before the School Board where he was given the option to either comply with the supervisor's order or to resign. "That was the end of that," said Battiste."I was gone."[possible link to racism] It was then that he went to Los Angeles with two buddies, intending to play jazz, where he met Bumps Blackwell, who was always trying to get music out of New Orleans. "This was back in the days of Fats Domino[link], and Bumps had a cat named Little Richard." Bumps paid Battiste to come back to New Orleans as a talent scout; when he returned to L.A.the company was trying to record Sam Cooke, then a gospel singer, and sell him as a pop artist using the song, "Summertime." At Bumps's request, Harold istened to Cooke's songs, found one called "You Send Me," and suggested some lyrics and arrangements.They proposed the song as the flipside, the throwaway, to "Summertime." The owner of the company didn’t like what Blackwell and Battiste were doing with Cooke ("trying to get him to sound like a white guy") because he liked the Little Richard sound.He told Bumps to take Sam and the song in payment for money owed him, and another label put the record out and hired Battiste. For many years Battiste was musical director for Sonny and Cher; three of the five gold records on his wall represent work he did with them. "When I first met Sonny, he was driving a meat truck.But he was a very intelligent, hard-working guy." Battiste let Mack Rebbenack work on the show. "Mack was always in trouble; I was always trying to keep him from crashing." In pursuing the topic of Rebbenack, Battiste reflected laughingly,“I brought him into the studio and did the Dr. John thing--it was almost like a joke.I didn’t think I was creating anything that would change his career.Another cat was going to be Dr. John[link].Mac didn't think he was a good enough singer. Well, he wasn't.But he didn’t need to be." Early in his career, Battiste founded AFO (All For One )[link] records, a company that invested the musicians themselves with ownership of their music., Although the second production of the company was Barbara George's hit "I Know," Battiste found that his talents lay elsewhere when faced with the business of music.The label went dormant until after his return to New Orleans in 1989 and now offers the same thing to young performers today as it did to Ellis Marsalis [link] and Alvin Batiste so many years ago--documentation of their work and a platform to get started from. Its main concentration is UNO students--basically "a bunch of students who . . . graduated through our program.[link to school?] In reply to a question about the differences of life in LA and New Orleans, he said, "The LA thing provided a base to expand from, enabling me to do things I couldn't do if I stayed here--movie scores for "Cannery Row," "Beyond the Valley of the Dolls," all the work for Sonny and Cher." But it is clear that the spirit and mission of AFO reflect his roots in the unique New Orleans sound, and his thoughts on the city and her music are best expressed in his own essay "The Spirit of New Orleans"[link] Harold saw that I was having trouble separating the different genres--blues, jazz, rock and roll--tryingto frame the question, "Where do you see it going" He said, "These words are going to move out of the way.The lines that separate, say, jazz,are created by words, and these lines are constantly being crossed.I hope that the words will get out of the way and let the music just be the music so that people won't have to make a decision.Say, "I like this piece of music, but I don't care what you call it." It's like racists "you can't say, "I don't like white people" or "I don't like black people," because it's not true.There may be one or two you don't like, but maybe that's just them.Maybe everybody else doesn't like them, too.Music hopefully will escape a separation like that." This wonderful, engaging man is so humble that he was genuinely astonished at the list of his musical accomplishments [link] that I had gotten from the Internet. When I quoted his friend, Kalamu ya Salaam, who said, "Fifty years from now, Harold Battiste will be looked on as one of the major forces in the development of New Orleans music in the last half of the twentieth century," he bowed his head and murmured, 'Well, I don’t know about that." I pressed.'Do you realize the gift you’ve given when someone like me, who can't remember the group or the name, does remember the lyrics, and for sure remembers the music? Your music?" Harold Battiste smiled, chuckled, and softly said, "Well, it is gratifying to hear one of those things on the radio and think, "Damn, they’re still playing that." |

||||||